When considering what to write, we often think first of ideas, but we'd do well to recall the words of William Carlos Williams, "No ideas but in things." Williams wasn't knocking ideas, just pointing out that they have roots in the concrete particulars of daily experience. Thoughts grow from what we see, taste, smell, and feel: morning steam on a mountain lake, a strawberry dipped in cream, or a crowd squeezing into the subway.

When we read a book, attend a concert, or simply visit with a friend, we perceive the world through our senses. William Blake called the senses. "the doors of perception." By opening or closing these "doors," we control the amounts and kinds of input we receive. In class, our ears hear the teacher's words and tone of voice, the intonations and rhythms in her speech. At the same time, our eyes see her changing facial expressions and fluttering hands, the way she leans on the lectern, then paces from desk to window. These sensory details are all parts of the class, and perceptive writers will note them.

William Blake called the senses "the doors of perception."

In fact, though, we aren't as aware of our environments as we might be. A college basketball game, a lunch at the student union, even a quiet walk in the woods could overwhelm us with stimuli if we don't limit what we take in.

Though ideas help us organize and sort this perceptual flow, we can't think about what we aren't aware of. Sensory data is the raw material of writing. To extend your awareness of your subject, take time to see, taste, hear, smell, and touch what you're writing about. Remove the veil of habit and see the true subject of your writing-not ideas and opinions, but the thing itself./p>

For instance, if you're writing a report showing why your office needs a new copy machine, you could start by studying the present one. You could note its size and jot down the exact dimensions. You could describe the worn rubber mat on the copy plate. You could point to the glass plate itself, scratched and difficult to align papers on. You might also describe how the copies look, tell how the paper is loaded and how often the machine jams, whether it makes enlargements and reductions easily.

These details and a hundred others can provide your report's content. You don't have to think them up or imagine them, just notice them and write them down clearly and accurately. This habit of alertness and attention to detail is essential. The more you get involved with your subject, the more you'll find to say about it.

Activities

1.7 Select an object you have with you now-a pen, a ring, a watch, a shoe, a book-and start writing about it. If you have a favorite possession with you, that's fine, but what you pick isn't important. Almost anything will do. Describe the object thoroughly. What is its shape, its color, its texture? How long is it? Does it make a sound? Does it show signs of age? Does it have any taste or odor? Concentrate on asking and answering questions about the item itself rather than telling where you got it or how you feel about it.

Don't worry about grammar or mechanics; just get down a clear and complete a description. Do notice, though, how much you can find to say about even the most trivial and unpromising subject when you concentrate on observing and recording details.

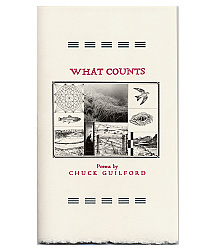

1.8 Select a book-any book. Begin writing down as many actual details about it as you can. What is its title? Who is its author? How many pages does it have? When was it published? By whom? Does it have a preface? What are its major divisions? Its subdivisions? What color is it? Just keep writing.

Don't give ideas or judgments about the book. Just give the facts. Write for about twenty minutes. At the end, write a one sentence wrap-up statement to tie your observations together and give a sense of completion. If you wish, use this sentence to offer an overall impression of the book, based on the details you've observed and recorded.